But a new interception technique is now showing that the onetime-use key and other information about the cards can be compromised in a new process called “shimming”.

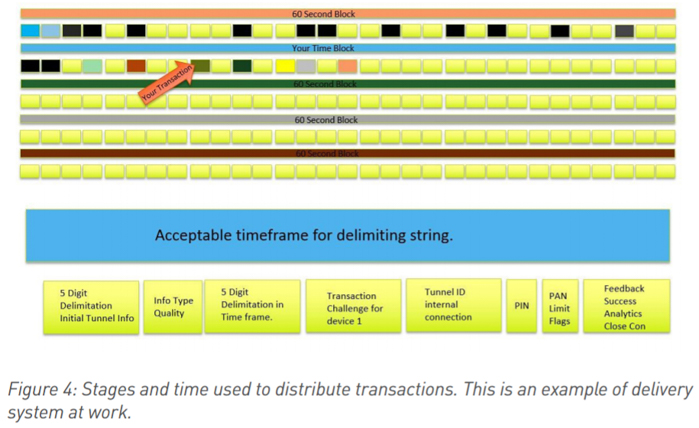

At last week’s Def Con 24 security conference in Las Vegas, Rapid7 security firm researcher Weston Hecker demonstrated that the 60-second window in which an EMV chip and terminal create a one-time encrypted transaction is too long a timeframe, and that it should be reduced from 60 seconds in order to provide more defense against a new proof of concept attack shown during the event.

EMV 60-second transaction timeframe needs to be reduced

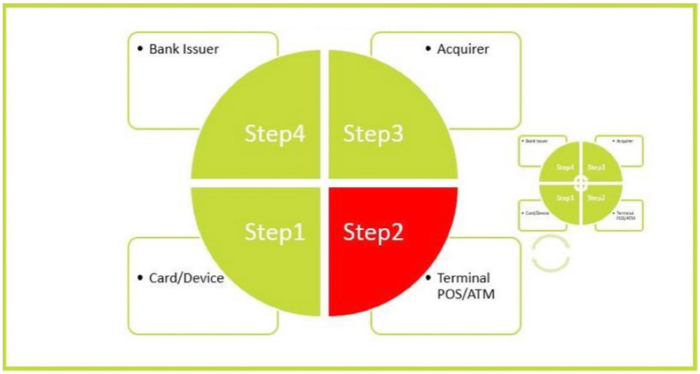

Weston Hecker’s proof of concept EMV hack requires at least two devices to be compromised. First, either a Point of Sale (POS) or ATM machine need a piece of hardware installed that reads the EMV chip – also called a “shimmer.” Second, the data captured by the compromised POS or ATM needs to be sent to another ATM machine that’s been compromised by a hardware hack which Hecker calls “La-Cara.” Basically, “La-Cara” is an automated cash-out machine that works on current EMV and NFC ATM machines and tricks the ATM into believing the physical card is being inserted. At this point, a robotic hand enters the PIN number, usually concealed behind an "out of order" sign so pedestrians and nearby customers cannot see it.

Source: BlackHat.com

Needless to say, the ATM machine being covered with an “out of order” sign to prevent any suspicions about a robotic hand sticking out of the front terminal is funny, but unfortunately realistic. Hecker claims that there was a cash machine near his house with an “out of order” sign that had gone without maintenance for a few days. He called the bank for an update, only to be told that the bank was unaware the machine was out of order.

Source: BlackHat.com

Hecker has published a very informative paper titled “Hacking Next-Gen ATMs: From Capture to Cash-Out” that demonstrates “La-Cara” and hopes to inform EMV merchants and private ATM owners of the steps they can take to mitigate the installation of foreign hardware devices. He claims that reducing the 60-second timeframe to complete a uniquely encrypted EMV transaction is the most important step that should be made more secure.

Attack could show up after October 2018

While this proof of concept attack isn’t expected to happen in the next few months, Hecker doesn’t expect this type of system could show up in the wild until around October 2018. Although the liability shift for fraudulent charges from magnetic swipes took effect in October 2015, industry consensus is that businesses will have until October 15, 2018 to complete the technology transition. After this timeframe, the “swipe and sign” feature on all point of sale machines will be turned off.

History of EMV contactless payments in the US

The three-year timeframe between 2011 and 2014 is when the majority of large U.S. banks began rolling out EMV cards to their cardholders for domestic use. Wells Fargo was one of the first U.S. banks to jump into the EMV ring, launching a pilot program in Spring 2011 and offering chip cards by invitation to Visa Signature cardholders in 2012. Citi Bank followed suit in August 2011 when it started issuing Corporate Chip and PIN cards for corporate cardholders traveling abroad. In June 2012, American Express began offering contactless EMV chip-based cards for all issuers of its cards in the United States, requiring all processors to accept American Express EMV transactions by April 2013. In February 2014, Chase began offering chip-and-PIN credit cards as part of a larger company effort to reduce fraud. Bank of America followed suit in September 2014 with its rollout of EMV cards, claiming it was the first U.S. bank to add the chip technology to consumer debit cards.

In the long run, the US has slowly seen companies like Visa and MasterCard encourage retailers to accept EMV-enabled cards, calling them to upgrade their machines by April 2013. This push didn’t work too well, and over the course of the next year and a half, a variety of massive security breaches occurred that prompted the United States to eventually issue federal guidelines for implementation of the EMV technology standard.

On October 17, 2014, President Obama signed into law an “Executive Order for Improving the Security of Consumer Financial Transactions” in the wake of several large-scale financial industry data breaches. These included a J.P. Morgan Chase leak affecting 76 million households, a Target retail credit card attack affecting 40 million customer records, a Home Depot malware attack affecting 56 million payment cards, and an Adobe attack compromising 2.9 million customer names, encrypted credit or debit card numbers and expiration dates relating to customer orders.

Section 1a basically states: “No later than January 1, 2015, all new payment processing terminals acquired in these ways shall include hardware necessary to support such enhanced security features.”

On January 21, 2015, the US General Services Administration announced that the official rollout of Chip and PIN cards would begin in January 2015 where more than one million charge cards were expected to be issued throughout that year. However, the GSA admitted that not all merchants would be chip-and-PIN ready by the end of 2015 (many retailers still cover their EMV terminals with written notices encouraging customers to keep swiping their magnetic cards). Going into the second half of 2016, many major retailers have been reluctant to make any mandatory switch and still accept magnetic swiping as the primary method of card transactions.

Since October 2015, US retailers still not accepting EMV as a payment method have been liable for fraudulent charges made at their stores. This policy effectively began shifting blame for counterfeit cards away from financial institutions and onto local store owners. However, US fuel merchants are exempt until October 2017, before the Fraud Liability Shift (FLS) policy takes effect for automated fuel dispensers at gas stations and convenience stores.

"It seems crazy that all of this money is being spent to send out replacement cards and to install all the new payment terminals at these big-name stores, but nothing has really changed - the security is no better," says Edgar Dworsky, founder of ConsumerWorld.org. "Plus, it's really frustrating and confusing for shoppers who see the new terminals and don't know whether to swipe or dip their credit card."

Of course, making the switch to chip-and-PIN technology is a costly process that requires retailers to not only install new card readers, but also integrate new software, receive certification for their upgraded payment system, and then train employees on how to use the new readers. Mallory Duncan, senior vice president and general counsel at the National Retail Federation, says it takes the average retailers “about 19 months to get the new chip card payment system up and running.”